Last year was the most turbulent year ever for nickel trading. In March, the price of this metal shot up like a rocket. The management of the London Metal Exchange, a 145-year-old institution, decided to suspend trading. Not only that, but the LME canceled all of the previous day’s trades, much to the anger of market participants who had just profited from the huge price increases.

Today, things have calmed down, and prices are moving at more or less normal levels. However, confidence in the LME has taken a huge hit, and there is a risk that prices will move sharply again. Demand for nickel is expected to explode, and the main producer, Indonesia, has plans to form a cartel.

The March 2022 price spike, in which the price of nickel shot up to $100,000 a ton in a matter of days, resulted from a spectacular variation of a so-called short squeeze. A short squeeze occurs when traders take a position speculating that prices will fall. In commodity markets, short positions are widely used by producers. They hedge the risk of a price decline in their inventories. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, nickel prices spiked while there were many short positions.

Short sellers need to add money as the price rises to cover the potential loss. If they cannot or will not do so, their positions are closed out with a buy order. This cycle of continuous buy orders to close out short positions causes the price to rise, exacerbating what is known as a short squeeze. According to the LME, things got so out of hand in nickel that the exchange had to intervene. The amounts to be deposited were so high that a wave of bankruptcies would follow. The LME called it the “spiral of death.”

Since then, limits have been set to prevent prices from moving too far. Nevertheless, that has not restored confidence. Hedge fund Elliott and trading house Jane Street took the LME to court. Now there is less trading on the metal exchange, so volatility is still high, and the limit is quickly reached.

As a result, something else is happening in the nickel market, far away from London’s LME trading floor.

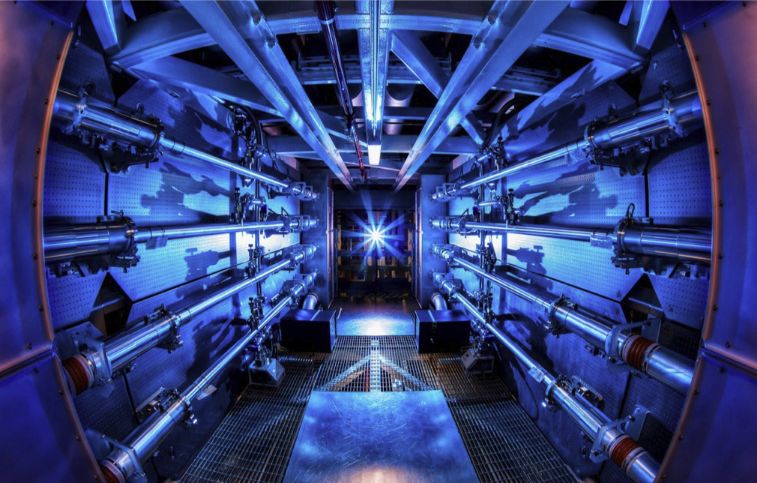

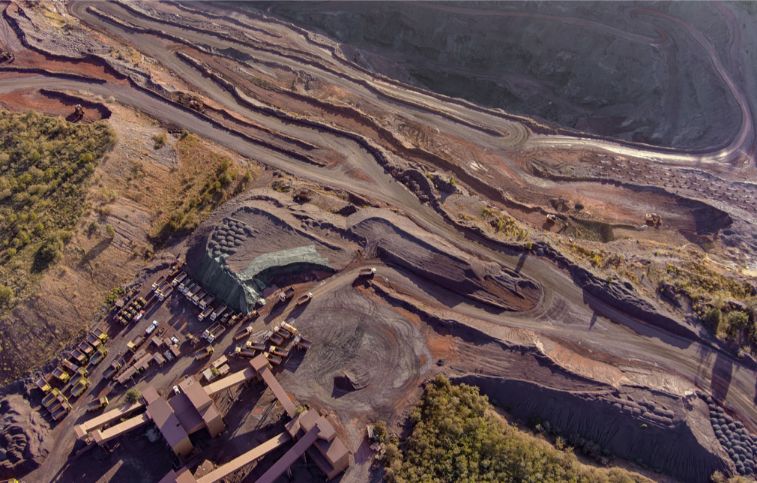

The world’s largest nickel producer, Indonesia, wants more control over supply. In November, the country proposed the formation of nickel-producing countries along the lines of OPEC, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. The formation of a “nickel cartel” is a bogeyman for buyers of the metal. Nickel is used in batteries, among other things. It is not without reason that Elon Musk, the founder of Tesla, warned of shortages years ago.

Indonesia’s nickel is now mainly used for stainless steel, not batteries. The country also wants to develop factories to supply the raw material for batteries. In this application, demand is expected to grow the most due to the rise of electric cars.

An alliance with other countries could help, but analysts point out that this is not easy. “Oil production in OPEC countries is state-owned,” says Ewa Manthey, commodities strategist at ING. “In Indonesia, it is not. They are private companies, like China’s Tsingshan and Brazil’s Vale.”

During a November meeting with Canada’s international trade minister, Indonesia’s investment minister proposed a “nickel-OPEC” plan. Canada is a major nickel producer, along with Russia and Australia, but Indonesia is the largest. The plan has been met with skepticism. An Australian association of mining companies argued that companies would never cooperate in a cartel. According to Bloomberg news agency sources, there is little support for the proposal within the Canadian government.

Nevertheless, nickel traders have plenty to be nervous about, even without a cartel. The sanctions do not yet cover nickel from Russia, but that could soon change. Moreover, according to a study by the International Energy Agency, the world will need 19 times more nickel by 2040 than it does today. The task of meeting all that demand is difficult enough without cartel schemes, sanctions, and a dysfunctional metals exchange.