Before the summer, European leaders decided to halt Russian oil exports to contain Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Now, six months after it was announced, the European oil embargo against Russia has gone into effect.

The European Union prohibits the importation of Russian crude oil transported by ship. Oil imported through the Druzhba pipeline into Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia is an important exception since these countries would otherwise face supply problems due to a lack of alternatives.

Furthermore, Europe, other G7 nations, and Australia have recently imposed a global price ceiling to prevent Russia from profiting excessively from oil exports to other regions. Specifically, other nations can only purchase Russian oil if the price per barrel does not exceed $60. This is comparable to the range of $55 to $65 per barrel that existed prior to the invasion of Ukraine.

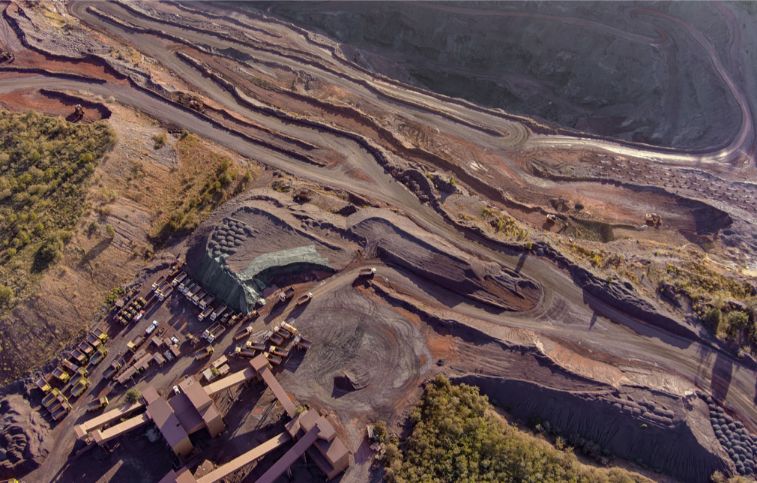

As a result of the sanctions, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ability to fund his war machine will be reduced by billions of dollars. Russia, the second-largest exporter of oil in the world, is heavily dependent on exporting oil shipments to other countries. In fact, over fifty percent of Russian exports end up in Europe. European officials hope the price cap will prevent Russia from selling its oil to other nations at a higher profit.

The shipowners from Europe and the G7 must follow the embargo, and other nations cannot enter Europe for 90 days if they break the embargo. In order to enforce the embargo, insurance companies are expected to follow the new policy. For example, they will no longer be able to insure cargo going to Europe or other places at a price higher than the cap. This could be a problem for Moscow because much of its oil trade goes through European insurers or the London Lloyd’s market.

As with other embargoes, it is anticipated that shipments will circumvent this rule by mixing cargoes of various origins at sea or by transshipping cargo at ports. Market analysts say Russia has built a 100-ship “shadow fleet” to counter the embargo. This shadow fleet of ships includes some previously used to transport oil for Venezuela or Iran secretly.

One criticism of the price cap is that $60 per barrel is still relatively high. Considering average production costs between $30 and $40 per barrel, the cap still allows Russia to profit from oil exports. Poland and the Baltic States had said they wanted a much lower ceiling, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky would have preferred a ceiling of $30. “Higher ceilings,” he said, “would still provide too much revenue for the terrorist state.”

Analysts argue that what is not yet present may still come to pass. According to Maria Shagina, a researcher at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Berlin, any agreement is preferable to none. “Now that the system exists, the screws can be tightened quickly by lowering the ceiling,” she explains.

Europe has already planned the second phase of oil sanctions. This time, they intend to ban petroleum products in February. As a significant supplier of diesel, Russia will undoubtedly feel the effects of such a ban. Nevertheless, it will be difficult for Europe to find alternatives, given that the continent requires more diesel refining capacity. Europe can buy shiploads from other regions for now, but this would cause competition with other regions and possibly cause price spikes.

Several countries have already initiated measures to circumvent potential diesel supply issues. The Netherlands has decided to increase strategic diesel supplies this summer. This will help reduce its dependence on oil from Russia, which was still 33% of its crude oil last year.